Healthcare’s Invisible Barrier: The Critical Role of IAQ in Infection Prevention

CLEAN Lessons Learned

Healthcare’s Invisible Barrier:

The Critical Role of IAQ in Infection Prevention

In the fifth installment of our CLEAN Lessons Learned series, focused on indoor air quality (IAQ) and its role in infection prevention in healthcare settings, we explored the critical impact of IAQ on controlling the spread of infectious diseases. This session, brought to you by the American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) and the Integrated Bioscience and Built Environment Consortium (IBEC), highlighted the essential link between theory and real-world application for improving healthcare safety through better air quality management.

During this session, we uncovered the importance of improving indoor air quality standards and adopting innovative technologies to reduce infection risks in healthcare facilities. We discussed practical approaches, including ventilation improvements, filtration technologies, and the need for updated performance standards, to protect vulnerable populations in healthcare environments from airborne pathogens.

Watch the recording or read the transcription to delve into the key takeaways on how IAQ metrics intersect with infection control strategies, emphasizing the need for layered approaches to managing health risks in hospitals and healthcare facilities. The panel featured distinguished experts from Yale University, SafeTraces, The Safer Air Project, Routt County Public Health, and Tobacco Free Portfolios, who brought valuable insights into the challenges and solutions needed to enhance infection prevention through improved IAQ.

Let’s continue leveraging the expertise shared in this session to foster safer indoor environments in healthcare and beyond.

- IAQ’s Critical Role in Infection Prevention: Improved indoor air quality is essential in preventing the spread of infectious diseases in healthcare settings, where patients are particularly vulnerable.

- Layered Protection Approach: A layered approach, including ventilation, filtration, and masking, is necessary to manage infection risks effectively and ensure that healthcare environments are as safe as possible.

- Education and Awareness: Healthcare professionals and facility managers must be educated about IAQ, its importance, and how to interpret air quality data. Understanding the “why” is key to driving change.

- Need for Performance Standards: Current IAQ guidelines and recommendations are not enough. Legally enforced performance standards, such as ASHRAE 241, must be implemented to ensure consistent infection risk management across healthcare facilities.

- Monitoring and Measurement: Continuous air quality monitoring, including CO2 levels and other IAQ metrics, is crucial for maintaining safe environments. Monitoring helps detect risks early and inform necessary adjustments to ventilation or other controls.

- Cost-Benefit of IAQ Improvements: Investing in improved air quality leads to significant long-term financial benefits, including reduced infection rates, fewer long-term complications like long COVID, and decreased liability risks for healthcare systems.

- Technological Innovations: Technologies such as portable HEPA filters, germicidal UV (GUV), and advanced building control systems should be considered infection prevention strategies, especially in high-risk areas like hospitals and long-term care facilities.

- Impact Beyond Healthcare: The lessons learned from improving IAQ in healthcare settings should extend to other public spaces, such as schools, long-term care facilities, and workplaces, to protect vulnerable populations everywhere.

- Leadership and Advocacy: Strong leadership is needed to prioritize and implement IAQ improvements. Advocating for cleaner air in healthcare is a matter of public health and social equity, ensuring safe spaces for everyone.

- Infection Risk Management Mode: Infection risk management should be an ongoing priority in healthcare, not just in response to new pathogens. Consistent IAQ management can help prevent both known and emerging infectious threats.

Erik Malmstrom

Chief Executive Officer at SafeTraces, Inc.

Erik Malmstrom is the CEO of SafeTraces, a market leader in technology-enabled testing, verification, and commissioning of HVAC and air cleaning systems to optimize indoor air quality and energy efficiency. With NIH, FDA, and DoE support, SafeTraces has pioneered a novel technology leveraging DNA-tagged particles that safely simulate infectious aerosols for real-world measurement and verification of airflow, air balance, particle removal, and germicidal efficacy of UV-C fixtures. SafeTraces provides one of four qualified testing methods for ASHRAE Standard 241, and its UL Verified Ventilation and Filtration mark tracks to CDC’s health-based ventilation guidelines. SafeTraces proudly supports leading corporate, government, and institutional clients, including Amazon, the US Department of Defense, and the Mayo Clinic. Erik received his undergraduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania and a joint MBA-MPP from Harvard Business and Kennedy Schools. He is a combat veteran and graduate of US Army Ranger and Airborne School.

Richard Martinello

Professor of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine

Dr. Richard Martinello is a Professor of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at the Yale School of Medicine. He is board-certified in adult and pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Martinello is the Senior Physician Director of Infection Prevention for Yale New Haven Hospital and the Yale New Haven Health System. Before this, he served as the Chief Consultant for Clinical Public Health for the Department of Veterans Affairs. In these roles, he leads teams focused on developing programs, policies, and processes to prevent healthcare-associated infections, including preventing respiratory virus infections, optimizing the care of persons with chronic viral infections, and improving the safety and quality of care provided to patients. He leads an active research program funded by the CDC for work focused on improving infection prevention and control. Dr. Martinello is a member of the Board of Directors of the International Ultraviolet Association (IUVA) and a co-chair of the IUVA Healthcare Working Group. In these roles, he has informed the development of guidelines and standards for applying UV for disinfection in healthcare and public spaces.

Plum Stone

Founder, The Safer Air Project

Plum has worked in health policy and public affairs for the last 20 years, with experience in the UK Parliament, international public affairs agencies, and in-house for patient advocacy organizations. Plum wrote her undergraduate dissertation on learning the lessons of past pandemics to prepare for future pandemics and has an MSc in Public Health (Nutrition).

At the pandemic’s start, Plum’s family were infected, and she lost her sense of taste and smell for two weeks. Ten days in, Plum’s 3-year-old daughter suffered a prolonged status epilepticus seizure and was hospitalized. Both Plum and her daughter were ‘previously healthy’ and had no known risk factors for serious illness. Unfortunately, by April 2020, Plum began developing symptoms now known to be long COVID. Adding to the family risk, Plum’s husband also needs a kidney transplant and, therefore, remains at significantly increased risk from any infection.

Plum’s professional background and personal lived experience have led her to found The Safer Air Project, which aims to make indoor air safer for everyone by recognizing indoor air quality as a critical accessibility and inclusion issue for people living with chronic health conditions.

Roberta Smith

Director of Public Health, Routt County

Roberta Smith, MSPH, RN, CIC, CIH, has over 25 years of experience in public health, occupational health, industrial hygiene, safety and infection control. She holds Bachelor of Science degrees in environmental health and nursing. She has a Master of Science in Public Health, is certified in Infection Control (CIC), and is a Certified Industrial Hygienist (CIH).

Currently, Roberta serves as the Director of Public Health for Routt County in Colorado, where she built a health department from scratch during a global pandemic. Now that the crisis is settled, she focuses on directing the department’s data collection practices and leading the public health clinical team for services such as immunizations and communicable disease surveillance.

Her career includes key roles like Infection Preventionist and Occupational Health Director at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Occupational Health Program Manager at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, and Director of Worker Health at Cority/Axion Health.

Roberta is a member of the National Association of Professionals in Infection Control (APIC) and the Mile High Chapter. She is active in the national and local chapters of the American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA) and is a member of the AIHA’s Infection Prevention working group. She has been recognized for her publications and leadership in industrial hygiene and public health. Throughout her many experiences, she still strongly encourages hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette wherever she goes.

Bronwyn King

Special Advisor - Clean Air, Burnet Institute

Dr. Bronwyn King AO began her medical career working as a doctor on the lung cancer ward at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia. While doing her best to treat her patients (many of whom had started smoking in childhood), Dr King observed first-hand the truly devastating impact of tobacco – many deaths and much suffering. She was unaware that, at the very same time, she was investing in Big Tobacco via her compulsory superannuation (pension) fund. Tobacco-free Free Portfolios was set up in response to that uncomfortable discovery. Since then, Dr King has assembled an accomplished team that has been instrumental in advancing the switch to tobacco-free finance globally. Her 2017 TEDx Sydney talk on tobacco-free finance has been viewed more than three million times.

A former elite swimmer who represented Australia and worked as Team Doctor for the Australian Swimming Team for ten years, Dr King is also an Australia Day Ambassador and an Ambassador for Big Brothers Big Sisters Australia. Dr King has received numerous awards in recognition of her unique contribution to local and global health, including being appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for distinguished service to community health and, in 2019, was named the Melburnian of the Year, an award bestowed by the City of Melbourne.

Georgia Lagoudas

Senior Fellow, Brown University

Dr. Lagoudas is a science policy expert, bioengineer, and passionate advocate for tackling complex challenges at the intersection of biotechnology, sustainability, and public health. Currently serving as Senior Fellow at the Brown University Pandemic Center in Washington, D.C., she leads groundbreaking initiatives focused on clean indoor air to reduce the transmission of infectious diseases. Prior to this, she played a key role at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, where she spearheaded the implementation of President Biden’s Bioeconomy Executive Order in 2022.

Her policy journey began as an AAAS Congressional Science and Engineering Policy Fellow, where she made significant contributions to biotechnology and climate policy in the U.S. Senate. She authored three bills, one incorporated into the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 as the “Bioeconomy Research & Development Act.” With expertise in international biosafety and biosecurity, Dr. Lagoudas also spent time at the Department of State’s Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation.

Before moving to Washington, D.C., she worked at DSM’s Innovation Center, where she led biotechnological projects to improve animal gut health and reduce antibiotic use in agriculture. Her work involved large-scale sequencing and data analysis to develop sustainable products.

Dr. Lagoudas holds a Ph.D. from MIT and the Broad Institute, where she developed cutting-edge microfluidic technologies to study microbial genomes and antimicrobial resistance. She has mentored numerous students and served as an MIT Communication Fellow. She enjoys outdoor activities such as cycling, trail running, and teaching as a NOLS Instructor.

Stephane Bilodeau 00:00

Good morning, afternoon, or evening, and welcome to IBEC’s live webinar session. I’m Stephane Bilodeau, Chief Science Officer at IBEC, adjunct professor in bioengineering at McGill University, and a fellow of Engineers Canada, based in Montreal.

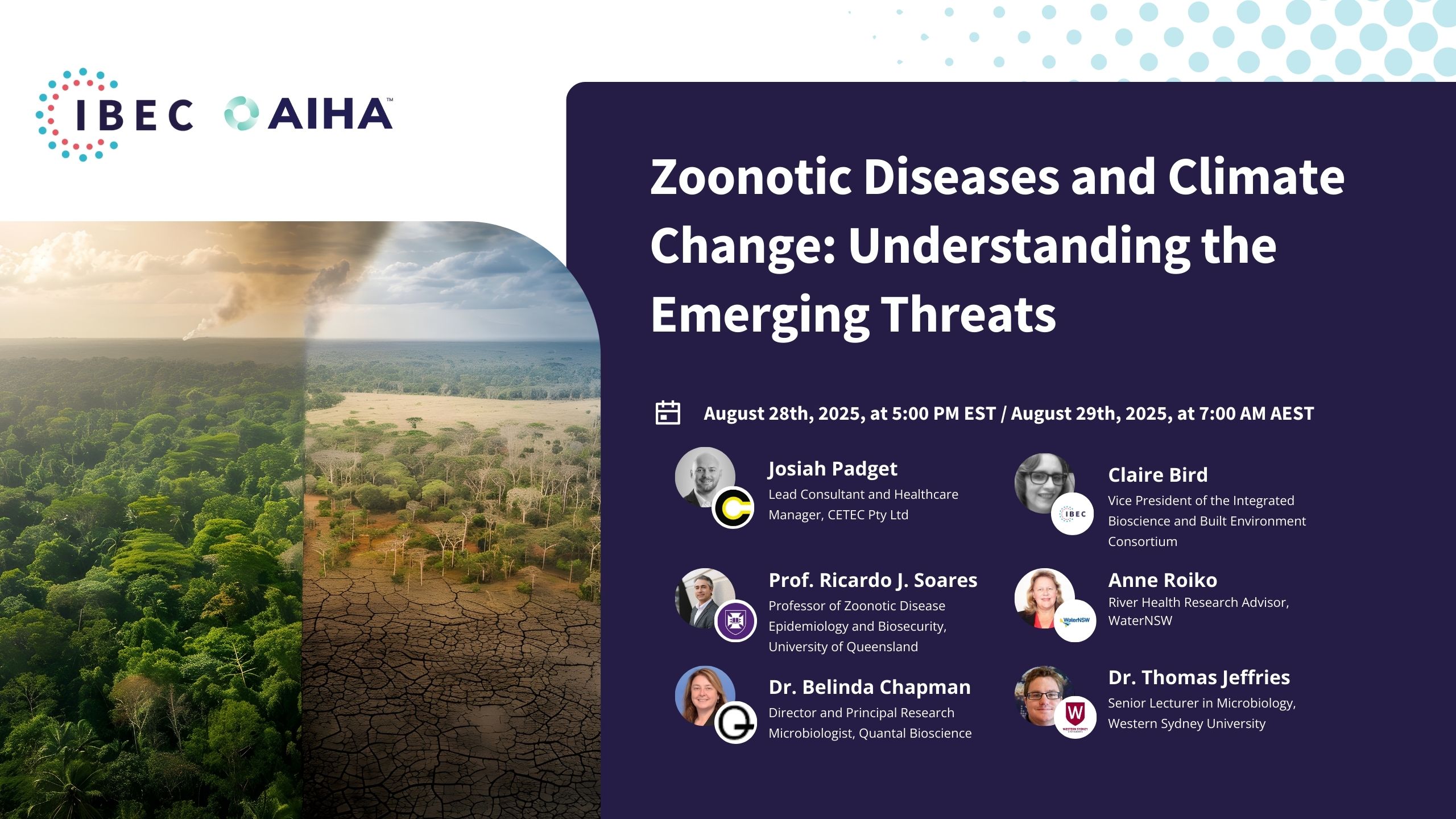

Today, we are at part five of our CLEAN Lessons Learned series on pathogens in buildings, titled Healthcare’s Invisible Barrier: The Critical Role of IAQ in Infection Prevention. Previous episodes in this and other IBEC series can be accessed free of charge through our website at weareibec.org/past-events. We are also planning three additional sessions focusing on avian influenza, climate change, and the impact on emerging infectious diseases.

Members of AIHA and other professional bodies from around the world are joining us today. At IBEC, we strongly believe in collaboration because bringing together various backgrounds and perspectives is key to bridging the gap between science and real-world applications. This is one of the reasons why I’m thrilled to be part of IBEC, the Integrated Bioscience and Built Environment Consortium.

Today’s session is a great example of that consortium in action, as we bring together expertise from different locations and perspectives, with contributors working in or being part of different healthcare systems.

The discussion will undoubtedly emphasize our shared mission while also shedding light on the differences between various professionals and their personal experiences. With the help of our four panel members and an incredible pair of moderators, Georgia Lagouda, whom you just saw, and Erik Malstrom, we will hear important voices from both the U.S. and Australia about the risks faced by those working in and attending healthcare facilities.

We hope this session will push forward the journey to overcome the impacts of poor indoor air quality on our patients and healthcare workers. The focus will be on how technology and policy should interact to see the implementation and raise awareness of buildings that provide safer, shared air for everyone.

I’ll first introduce our moderators, and then invite each panel member to say a few words about their work and interest in today’s discussion. Our speakers, moderators, and scientific advisory board members have kindly presented questions they feel would be best addressed by the panel. We will start by posing a few of these before opening the discussion to the audience.

We encourage you to add your questions to the Q&A box as they come to mind. If your question isn’t answered today, we will do our best to forward it to the panelists after the session. Please make sure to specify who your question is directed to, or send your question to a specific panel member afterward by emailing info@weareibec.org—you’ll see the email address in the chat.

At the end, we will bring you up to speed with IBEC’s latest work and explain how you can engage with us now and in the future. Without further ado, let’s get started.

As I mentioned, our moderators today are Erik Malstrom, CEO of Safe Traces, and Dr. Georgia Lagouda, Senior Fellow from the Pandemic Center at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

Erik and his team at Safe Traces have developed a novel diagnostic and software platform leveraging DNA-tagged aerosol tracer particles that safely simulate the emission, mobility, and exposure to infectious aerosols. This platform helps assess, process, and mitigate airborne infection risks in real-world buildings. They work closely with leading building owners and operators, including Amazon, Google, the U.S. General Services Administration, the U.S. Department of Defense, and Mayo Clinic, to optimize indoor air quality, energy efficiency, and overall building performance.

Prior to his current work at Safe Traces, Erik has worked extensively in both industry and government and at the intersection of the two. He is an Army combat veteran and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard Business and Kennedy Schools. I’ll now turn it over to you, Erik, to introduce your co-moderator, Dr. Georgia Lagouda.

Erik Malstrom 05:49

Thank you so much, Stephane, and thank you to IBEC and the IBEC team for organizing today’s session. A big thanks to our excellent panelists, who you’ll be introduced to in a few minutes, and a huge thank you to the audience for joining us today.

I am very excited to be co-moderating today’s panel discussion with Dr. Georgia Lagouda, who is a leader and advocate for public policies and system change to improve health outcomes across the built environment. Dr. Lagouda is a Senior Fellow at the Pandemic Center at Brown University’s School of Public Health, with deep expertise in biosecurity, pandemic response, and indoor air quality.

Prior to her current role, she served as Senior Advisor at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, where she launched the Clean Air and Buildings Challenge and led an executive order on advancing the American bioeconomy. Georgia has also worked at the Department of State and in the U.S. Senate as an AAAS Science Policy Fellow, where she introduced three bills, one of which became law. She holds a PhD in Biological Engineering from MIT.

On a personal note, I saw Georgia in action at the White House, and she was truly one of the key leaders behind the impressive indoor air quality agenda launched by the current administration. It’s an honor to be co-moderating with her today. Welcome, Georgia—over to you.

Georgia Lagoudas 07:22

Thanks so much, Erik. It’s great to be with you today. I feel the same—it’s been excellent having such a strong partner in the private sector. There’s only so much the government and public sector can do, so it’s been fantastic partnering with you. I’m really excited to be here today with IBEC and this fantastic panel of speakers.

I’ll kick off some introductions, but first, I just want to express my excitement to talk about this topic, highlight the importance of indoor air quality (IAQ) in healthcare settings, and dive into some important questions. We have a great set of panelists with diverse experiences.

I’ll introduce our first two panelists and then turn it back over to Erik, who will introduce the rest.

First, we have Dr. Richard Martinello. He’s a professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the Yale School of Medicine, and he works on programs, policies, and processes to prevent healthcare-associated infections—very relevant to today’s discussion—including the prevention of respiratory viral infections. He also ensures that patients with chronic diseases receive optimal care. Dr. Martinello leads a CDC-funded program focused on improving infection prevention and control, and he serves as a board director for the International Ultraviolet Association, where he helps develop standards and guidelines for deploying UV technologies in healthcare settings.

Dr. Martinello also serves on the board of directors for his local public health district in Connecticut. He remains patient-facing and is board-certified in both adult and pediatric infectious diseases. Additionally, he serves as Senior Physician Director of Infection Prevention at Yale New Haven Hospital and the Yale New Haven Health System. We’re really excited to have you with us, Dr. Martinello.

Next, we have Roberta Smith. She’s a registered nurse, a certified industrial hygienist, and holds a Master of Science in Public Health. We’re thrilled to have Roberta with us today. She brings over 25 years of experience in public health, occupational health, industrial hygiene, safety, and infection control. She holds Bachelor of Science degrees in both environmental health and nursing, which puts her at the nexus of buildings, people, and pathogens—three cornerstones of IBEC’s mission.

Roberta is currently the Director of Public Health for Routt County, Colorado, where she built the county’s health department from scratch during a global pandemic, which has been truly phenomenal. Thank you for your work there, Roberta. She has since shifted her focus to data collection practices and leading public health and clinical teams in her work.

Thank you both for being with us. Now, back over to you, Erik.

Erik Malstrom 10:06

Great, thanks so much. Dr. Bronwyn King, AO, is pleased to be working with the Burnet Institute and the University of Melbourne to help advance Australia’s progress on indoor air quality, building on lessons from Australia’s world-leading approach to tobacco control. Dr. King has convened a series of IAQ parliamentary roundtables for Australian politicians and led the development of new collaborations and partnerships among a broad range of stakeholders, including academia, advocacy, industry, business, and government. In August of this past year, Dr. King was honored to brief the Australian Prime Minister on the issue of indoor air quality.

Dr. King is a radiation oncologist by background and the founder and CEO of Tobacco Free Portfolios, an NGO with a global footprint. In 2019, Dr. King was named Melbourner of the Year. Thank you so much for joining us today, Dr. King—I’m really interested to hear from you.

Finally, we have Plum Stone, the founder of The Safer Air Project, an advocacy organization that recognizes indoor air quality as a critical accessibility and inclusion issue for people living with chronic health conditions. Plum has worked in health policy and public affairs for the last 20 years, with experience in the UK Parliament, international public affairs agencies, and patient advocacy organizations. Plum wrote her undergraduate dissertation on learning the lessons of past pandemics to prepare for future ones, and she holds an MSc in Public Health, with a focus on nutrition.

She never anticipated that her life would be changed when her family caught COVID-19 early in the pandemic. Both Plum and her daughter suffered health impacts that have affected their daily lives, and her response has been to enact change by attracting leading minds from Australia and abroad across policy, indoor air quality, and medicine. She seeks to preserve the day-to-day lives of the Australian and global communities.

We have a really great panel today, with diverse perspectives in terms of their disciplinary backgrounds, geographies, and how they approach today’s topic. What we’re going to do now is turn it over to each panelist for about five minutes of opening remarks. We’ll start with Dr. Richard Martinello. Over to you.

Richard Martinello 12:36

Right. Well, thank you very much. I want to start by discussing the airborne transmission of infectious respiratory pathogens. If you’ll give me a moment, I’m going to pull up a slide to help illustrate the complexity of this process. You should be seeing it now.

I think we’ve learned an enormous amount over the last five years, particularly through our experience with COVID-19, about how infectious respiratory particles place us at risk for acquiring infection. We’ve moved from a time in healthcare when it was difficult to understand whether or not a pathogen was transmitted by small-particle aerosols in an airborne manner. We used to have a very stringent definition to identify those diseases.

It’s striking that diseases we’re confident are transmitted by airborne infectious respiratory particles—such as chickenpox, smallpox, and measles—are easily diagnosed due to the characteristic rash in affected individuals, allowing us to observe transmission over distances. However, for other respiratory viruses, including COVID-19 and influenza, we don’t have that opportunity. We can’t easily determine how someone acquired the disease through direct observation. I think we now have a better understanding of the complexity of the transmission of these infectious respiratory particles, although there is still much to learn.

Let me take a few moments to go over this figure. On the left-hand side, you can see someone who is contagious, generating infectious respiratory particles. There’s variation in the size of these particles—some are large enough to follow a ballistic path, landing close to where they are produced, unless the person is coughing or sneezing, in which case the particles can travel up to 10 meters. Importantly, there are also smaller infectious respiratory particles that remain aloft in the air and can be transmitted over long distances.

This transmission is further complicated by the fact that both large and small particles can deposit onto surfaces. Depending on the characteristics of the pathogen, those surfaces may remain contagious, leading to potential transmission when others come into contact with them. There are many ways these infectious respiratory particles can contribute to transmission in healthcare environments, and we worry about this constantly. Indoor air quality, while often in the background, plays a critical role in protecting us, especially from the long-range transmission of these particles.

In healthcare, we usually think of these particles as transmitting viruses and bacteria, but I want to emphasize that in hospitals and certain ambulatory settings, a significant portion of our patient population—up to 5-10%—can be severely immunocompromised. This status puts them at higher risk not only for severe viral or bacterial infections but also for fungal infections. We pay close attention to indoor air quality to minimize the presence of fungal spores, which are often introduced from outdoor air. Filtration is a key measure to remove these spores from the air.

The last thing I’d like to mention before we move into our discussion is surgical site infections. Although we don’t usually think of surgical site infections as being related to indoor air quality, they certainly can be. About seven years ago, there was an incident involving a device used in operating rooms. This device, which was sold globally, was contaminated during manufacturing. It contained a fan and water used to cool blood flowing through the device. Unfortunately, the fan aerosolized a mycobacterium contaminating the device. The particles entered the air in the operating room and settled into surgical wounds, leading to hundreds of infections worldwide.

This incident highlights the complexity and diversity of infections that can be prevented through attention to indoor air quality. With that, I’ll stop my comments here. But first, let me thank IBEC and the organizers for inviting me to this session.

Erik Malstrom 19:00

All right, excellent. Thanks so much, Richard. That was really helpful in grounding us in the different transmission pathways and the medical and scientific aspects of this topic.

Now, we’re going to move to Roberta, who is joining us to share her experiences on the front lines as a public health leader and industrial hygienist, and she’ll build on Richard’s comments. So, over to you, Roberta. Thanks so much.

Roberta Smith 19:32

Thank you, and thanks to IBEC for having me today. I’d also like to wish a Happy International Infection Prevention Week to all my fellow infection preventionists out there doing the hard work.

Today, I want to put into perspective the roles and teams in healthcare working not only to understand indoor air quality but also other environmental factors. I really appreciate Dr. Martinello’s insights on how infections are transmitted in healthcare settings and the importance of considering the patient population. I’d like to expand on that by talking about the various teams in healthcare involved in infection control—teams like infection preventionists, industrial hygienists, and occupational health professionals. These groups should have a strong working relationship to understand what’s happening in healthcare settings.

For my industrial hygienist colleagues, the healthcare environment is different from what many of you might be used to. Patients aren’t workers, so when we look at sampling and other industrial hygiene practices, we need to understand the patient population and their chronic risk factors. There’s a lot of diversity in healthcare, and I also want to emphasize that healthcare is not limited to hospitals—it includes dental offices, physician practices, public health clinics, and long-term care facilities. It’s important to be inclusive of these different types of facilities.

In healthcare, sampling isn’t always a cornerstone in understanding disease transmission. It can play a role, but it’s more important to partner with surveillance, epidemiology, and microbiology labs to put the pieces of the puzzle together. Often, when sampling is done, it’s for an event that happened in the past, so capturing real-time information can be challenging. Ventilation systems in healthcare are designed for this unique environment, and any disruption—like construction or the introduction of new devices—requires a fine balance. We need to pay close attention when making changes in facilities to avoid unintended consequences.

When there’s an infectious disease transmission in a healthcare setting, it not only affects the patient or the facility—it also spills into the community. In public health, we often see these diseases transmitted to the broader community, so preventing infection in healthcare settings is crucial to stopping community spread.

I’m a visual person, so I’d like to share a couple of slides to help set the context and show the different roles involved in infection prevention. The nexus of safety, industrial hygiene, occupational health, and infection prevention is where teams collaborate, using the tools they know best to understand disease transmission and resolve issues in their specific environments. As an industrial hygienist, I always refer to the hierarchy of controls, and Johns Hopkins modified the NIOSH hierarchy for respiratory illnesses like COVID-19. When we’re dealing with infectious diseases, we can’t simply substitute them out—we need a different perspective for each facility and situation.

Lastly, I want to highlight that infection control isn’t just the responsibility of infection preventionists, industrial hygienists, and occupational health professionals. There are so many others in the healthcare setting involved in this effort. Communication is key—we need strong relationships and clear communication, in a language everyone can understand.

Disease surveillance systems are essential for tracking and communicating about infections. There are robust systems in place in public health and hospital settings, and infection preventionists play a critical role. These tools, combined with strong communication and collaboration, help us prevent infectious disease transmission and improve indoor air quality in healthcare facilities.

Erik Malstrom 26:56

All right. Excellent. Thank you so much, Roberta—lots of food for thought there. Anytime I see boxes with lots of different lines, it’s, needless to say, complicated, with many points where things could go wrong. But we’ll get into that later in the discussion.

Thank you again, and now we’re going to move out of the U.S., across the Pacific Ocean, to Australia. We’re pleased to have Dr. Bronwyn King, who is approaching this not only as a medical doctor but also as an advocate and advisor to high-level government officials in Australia.

Over to you, Bronwyn, and thanks so much for joining us.

Bronwyn King 27:42

Thanks so much, Erik. It’s great to be here, and a warm welcome from Thursday morning in Melbourne, Australia. It’s a beautiful day—not quite as beautiful as this background I have here, but it seemed fitting for today’s topic.

For my remarks, I want to break things down into four simple questions.

The first question is: Do we have a problem? Is there something that truly warrants our attention? The answer is a resounding yes. Hospitals, by definition, should be safe places. Patients are vulnerable, and that needs to be at the center of our thinking. Hospitals are also massive workplaces employing an extraordinary number of people worldwide, and it shouldn’t be controversial to expect them to be safe for everyone.

Unfortunately, the data shows that these expectations are not being met—neither in Australia nor across the world. We do have some data from Australia on hospital-acquired infections in patients. This data was incredibly difficult to secure, but after much effort, we obtained it from Victoria, New South Wales, and Queensland—three of Australia’s largest states by population. In 2022 and 2023, these states reported thousands of hospital-acquired infections, with death rates ranging from 5% to 10%. That’s a massive death rate for diseases acquired by people seeking care. And we’re not even accounting for long COVID, which is a significant consequence of COVID-19 that isn’t being measured at all.

In terms of healthcare workers, the data is even harder to find. However, back in 2021, in my home state of Victoria, there was a report early in the pandemic that 2,000 healthcare workers had acquired COVID-19. After much pressure, data was released showing that 70% of those workers contracted COVID-19 at work. Although this is just one small sample, it underscores that hospital and healthcare workers are at risk of infection while on the job—and this applies worldwide.

The second question is: Is there a solution? And again, the answer is yes. Airborne diseases require airborne precautions, and these are not routinely used in hospitals. As Roberta mentioned, there is a hierarchy of controls with multiple layers to protect people from airborne diseases, but few, if any, of these layers are in widespread use in hospitals globally.

In hospitals, we need unwell staff to stay home. Unfortunately, we’re seeing the opposite in many places where unwell workers are encouraged to come to work, which is completely unacceptable. We also need to test staff and patients—especially upon admission—to identify infectious diseases and ensure proper precautions are in place. Everyone in hospitals should be wearing N95 respirators or specialized masks, and indoor air quality standards should be implemented and maintained routinely, not just in specialized areas like ICUs or surgical theaters, but throughout the entire hospital.

Do these measures work? Absolutely. The Burnet Institute, where I’m working, recently published modeling that shows N95 masks and testing alone could save over 1,500 lives per year in Victoria and save over AUD $78 million annually (around USD $50 million). These simple measures can have an enormous impact.

The third question: Is the current situation with COVID-19 an outlier compared to other hospital-acquired infections? Again, the answer is yes. COVID-19 is getting a free pass compared to all other hospital-acquired infections. Richard mentioned wound infections—no hospital allows even one wound infection to go unreported. There’s an incident report, an investigation, and changes in policies and procedures. The same goes for bedsores and medication errors. Yet COVID-19 is not being treated with the same level of concern. It’s a serious problem that isn’t being addressed with the urgency it deserves.

Finally, why is there so little action and urgency on COVID-19? I believe there are three main reasons. First, COVID-19 has become a toxic word. There’s a global trauma that makes it difficult for people to talk about COVID sensibly. As communicators, we need to be strategic about how we address this, recognizing that COVID-19 is a deeply upsetting topic for many.

Second, there’s an overwhelming amount of misinformation about the true impact of COVID-19 and how it spreads. It’s shocking how many people still think washing their hands protects them from an airborne disease. This was a catastrophic error at the start of the pandemic, and we’re still fighting it today.

Third, there is a severe lack of leadership on COVID-19 at all levels—in healthcare, hospital management, and politics. There’s a beautiful quote by John Kenneth Galbraith that sums it up: “It’s far, far safer to be wrong together than to be right alone.” I feel that hospital leaders are clinging to the safety of doing nothing. It’s going to take real courage for someone to stand up and say, “This is unacceptable, and we’re going to make a change.” I can’t wait to see who that leader will be, and I hope others will follow.

Erik Malstrom 37:28

Thank you so much, Bronwyn. Great comments, and it sounds like you’re already one of those leaders! I’m tempted to direct it to Georgia here because she has a lot of experience and leadership in this area too. But you’ve certainly laid out a lot of issues regarding where we are right now, the path forward, and the challenges ahead. Thank you so much. I’m sure we’ll revisit many of those topics later in the discussion.

Now, finally, we’re going to have Plum Stone join us to give the last set of introductory remarks. Plum is also in Australia but originally hails from the UK. She’s doing impactful work with The Safer Air Project and has been personally affected by COVID-19 and airborne infectious diseases. Plum, we invite you to go ahead and present. Thanks so much for joining us.

Plum Stone 38:26

Thank you very much for having me. I’m just going to try and share my screen. Thank you. So I’ll talk a little bit about why shared indoor air is an accessibility issue and why everyone should be able to breathe safely, particularly in healthcare settings.

Eric has already kindly introduced me and shared some of my background, so I’ll skip over that and talk about my high-risk family and our experiences. At the start of the pandemic, I was living in the UK with my young family. Before the country went into lockdown, I lost my sense of taste and smell for two weeks. Shortly afterward, my three-and-a-half-year-old daughter suffered a prolonged status epilepticus seizure and was hospitalized. The hours between her receiving medication and waking up were the longest of my life. Over the next fortnight, she continued to experience other challenging symptoms and required several trips to the hospital. It was a very traumatic time for us.

As we went into lockdown, I began developing neurological and cardiovascular symptoms, which we now recognize as long COVID, and those symptoms persist to this day—four and a half years later. Both my daughter and I were previously healthy with no known risk factors for severe illness, yet we both experienced poor health outcomes from COVID-19.

To add to this, my husband has stage 4 autoimmune chronic kidney disease, meaning he’ll require a kidney transplant in the next few years. He’s at significantly increased risk of poor health outcomes from infections. My son Henry, pictured here, was also recently diagnosed with an autoinflammatory condition. As a family, we’re all at increased risk of poor health outcomes.

Because of my family’s experience and my 20 years working in public health policy and patient advocacy, I’ve spent many sleepless nights wondering what the solutions are to these problems. How do we, as a family, safely access healthcare, schools, and workplaces? And, of course, we’re not alone. People living with high-risk conditions like cancer, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and cardiovascular disease are not rare or isolated. We’re in every workplace, every school, every community, and especially in every healthcare setting.

In Australia, during the pandemic, health leaders would often say, “Don’t worry, the people who died had pre-existing conditions,” which led to the belief that these individuals were already terminally ill and that no one else needed to worry. This effectively “othered” people with chronic health conditions, which changed how we view our communities.

Now, looking at healthcare and airborne infections, here in Australia, we have the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights, which outlines seven rights that patients have. The three I’d like to highlight are access, safety, and respect. Everyone has the right to access care that meets their needs, is safe, and is respectful. But in the absence of indoor air quality standards and airborne infection prevention policies, these rights are not being met for patients. We’ve also discussed the rights of healthcare workers—workers have a right to a safe working environment, and the rates of long COVID among healthcare staff are rising, so we need to be mindful of that from both patient and healthcare worker perspectives.

To share an anecdote: my husband had a tonsillectomy last year, which was very challenging. In the weeks leading up to it, the New South Wales Health Minister announced that they were dropping masking mandates in healthcare settings. This meant my husband, who is severely immunocompromised, was going into surgery with no guarantee that healthcare workers around him would be masked. I reached out to ask about this, and I was told that he should speak to the infection prevention control team at the hospital. On the day of the surgery, despite our prior conversation, the agreed precautions were not in place. Because of the doctor-patient power imbalance, my husband felt unable to advocate for himself, and after the general anesthetic, he couldn’t advocate at all. When I arrived to pick him up, he was wearing an N95 mask, despite just having had surgery on his throat, while unmasked healthcare workers administered his medication, forcing him to remove his mask.

We need a paradigm shift in infection prevention control in hospitals. SARS-CoV-2 and other airborne viruses are constantly present in the community, with around 60% of transmissions occurring pre-symptomatically. We need to ensure that healthcare is safe for everyone and recognize that the current mortality rates from hospital-acquired infections, as mentioned earlier by Bronwyn, are unacceptable.

I’ll leave it there. Thank you very much.

Georgia Lagoudas 47:33

Thank you so much, Plum. That was incredibly helpful framing, and while it’s really important to hear about people’s personal experiences, it’s also challenging. I really appreciate your perspective on this.

Now, I’d like to invite some questions, and maybe we can bring the rest of the panelists to join us for a group discussion. We’d also love to hear from the audience—if you have specific questions for the panelists, Eric and I will keep an eye on the chat and raise those as appropriate.

I wanted to start with a question that builds on what we’ve heard so far. Rick gave us a great perspective on infections in healthcare settings and why that matters. We’ve heard from different angles on this issue, and I appreciated Bronwyn bringing in data to help us understand the scope of the problem. The answer is clearly yes—there is a problem.

From my perspective, when I was previously at the White House, we were working to figure out how, as a federal government, we could elevate this issue for broader awareness, which could then lead to action. But it takes time, and as Plum said, we need a paradigm shift.

So, let me start with the first question: What are we doing now in hospitals? What are the current standards? Rick, maybe I can turn to you to talk about the CDC’s ventilation guidance, which covers different types of rooms and settings in hospitals and other healthcare facilities. This group seems to believe that’s not enough—we should be doing more. Could you describe what we’re doing now and why that might not be sufficient? Then, I’d love to hear from one or two other panelists who might want to add to Rick’s answer.

Richard Martinello 49:25

Sure, thank you, Georgia. As you mentioned, when hospitals and other healthcare settings are constructed in the U.S. and many other countries, there are very clear building guidelines. These guidelines dictate the amount of ventilation required in a specific space and the level of filtration needed.

What we’ve learned through our experiences during the pandemic is the critical role ventilation and filtration play in preventing the longer-range transmission of infectious respiratory particles. However, that alone is not enough. We still have to address short-range transmission, which ventilation and central filtration are insufficient to prevent.

So, we have other options, and these were touched on in the hierarchy of controls. I’ll let Roberta expand on some of these, but masking was mentioned as well. We know that masks and respirators are both very effective, not just for personal protection, but also as a form of source control to prevent contamination of the environment.

During the pandemic, for example, we brought in portable HEPA filters to help contain the virus in areas that were insufficiently engineered to prevent transmission. These filters were also used to protect individuals who were at higher risk. However, managing hundreds of portable filters presented significant challenges.

So, while we’ve tried different approaches, it’s really the engineering controls that hardwire processes into our systems that are the most effective and manageable.

Georgia Lagoudas 51:32

Thank you so much, Rick. If I could add something before we hear from Roberta—I think we have a set of controls in place, but it seems like we need to reassess what an acceptable level of risk is for patients and staff in healthcare settings. How can we adjust the minimum engineering standards to better reflect that risk level?

Roberta, I’d love to hear your perspective on this as well.

Roberta Smith 51:59

Yeah, I was nodding along with Dr. Martinello. In healthcare, we have ASHRAE standards that have been updated and need to be considered in these settings. The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) at the CDC in the U.S. is also revising their guidelines. Many of the existing guidelines for healthcare environments were established in the early 2000s, and we’ve essentially been operating on status quo since then.

I believe there is now a movement to update these guidelines, ensuring things like proper pressure differentials and the correct filtration levels in specialized spaces. But it’s not just about having these guidelines and requirements in place—the people responsible for running and maintaining these ventilation systems need to know how to do it properly.

Sometimes, an HVAC tech might come from an office setting and not fully understand the unique needs of a healthcare environment. It’s crucial that they’re trained on these systems. For example, if you’re adding portable HEPA filters to a space, it could offset the balance of airflow in the room and potentially affect how air is being pulled from a negative pressure anteroom.

So, it all comes into play—we have these systems and standards, but the key is maintaining them and validating that they’re working correctly to protect both workers and patients in these vulnerable settings.

Georgia Lagoudas 54:02

Thanks, Roberta, excellent points. Erik, this might be a good time for you to jump in—we had chatted earlier about the tools we use in healthcare settings and how we know whether what we’re doing is effective. I’ll turn it over to you for that.

Erik Malstrom 54:15

Yeah, so I guess picking up on that. Bronwyn and others—Rick and pretty much everyone—spoke about how we have a good sense of what’s effective and data on what’s effective from an indoor air quality and infection prevention standpoint. The application of these tools is very inconsistent in many cases.

But also, there are other technologies beyond just what removes or inactivates particles or protective measures like masking and so forth. I’m wondering, in terms of the role of technology—of course, our company is a technology company, and we always look at ways that technology can help solve problems—I’m interested, from the panel’s perspective, what role do you see for technology in helping address these problems, whether it’s monitoring, vaccination, or actually controlling the air quality within spaces?

Maybe I’ll start with Bronwyn and then open it up to anyone else who feels motivated to answer.

Bronwyn King 55:27

Thanks, Erik. When we think about technology, it often feels like we’re waiting for something amazing to come along before we take action. But I think we should take a step back and remember that Florence Nightingale, with her hospital designs that allowed airflow from one side of the ward to the other, did an amazing job over 100 years ago. We already have many of the tools we need. We don’t need to wait another second to get started—we can implement simple measures using what we already have.

For instance, we can improve natural ventilation. In many aged care centers, residents’ rooms have windows that are not being opened, simply because people don’t understand the importance of natural ventilation. So, we need to maximize natural ventilation where possible, and where that’s not feasible, we can improve mechanical ventilation or make system-wide changes. Portable air purifiers are also being used in many hospitals, and while they’re fine as a temporary measure, they can help while we wait for more systemic building and engineering changes.

Germicidal UV (GUV) radiation has also been around for a long time but hasn’t been widely used in healthcare settings. Here in Victoria, we’re currently conducting a trial of GUV in aged care facilities, and we’re hoping to gather sharp data on its benefits. The trial will take a couple of years, but if the results show a significant benefit—not just for COVID-19, but for all infectious diseases—the goal is to roll it out across the aged care sector.

You mentioned consistency, and that’s where we’re really lacking in the hospital sector. Right now, every hospital is doing its own thing, and often that means doing nothing. I’ve engaged with major cancer hospitals around the world, and it feels like the management teams are comfortable doing nothing because they see no other hospitals taking action. That comfort in doing nothing is something we need to challenge. There are so many simple measures that we can implement right away, and we need to stop waiting for perfection. We just need to be better today than we were last week, and better next year than we are today—taking incremental steps forward.

Lastly, I wanted to mention something you brought up, Georgia, about acceptable risk. One thing that has been incredibly frustrating is that, in many hospitals, when COVID-19 levels are high, they implement stricter controls—masking, testing for patients upon entry—but as soon as the levels start to drop, they abandon the very techniques that have protected people in the hospital. It’s as if there’s a tolerance for patient death and COVID-related morbidity that I’ve never seen with any other disease. We need to remind ourselves that hospitals should be safe places, and we should always aim for no harm to patients. That principle should guide us as we think these issues through.

Erik Malstrom 59:16

Great. Would anyone else like to respond to that question about the role of technology?

Richard Martinello 59:25

Yeah, I think there are a few technologies I’m particularly interested in. One is UV. Ultraviolet (UV) light has been around for nearly 100 years since its germicidal properties were identified. Upper-room UV has been used for many decades, but it’s been underutilized in healthcare. That presents a potential opportunity. Something new that’s emerging as LED technology advances, along with other lighting technologies, is the application of far-UV. I think far-UV holds a lot of promise, but it’s going to require leadership, as noted earlier, to bring it into healthcare settings and create safer spaces.

Another technology that is often overlooked is our building control systems. These systems can incorporate additional variables, such as carbon dioxide levels or other measures, to help optimize ventilation and adapt spaces to make them safer. Building control systems, along with UV, are important because healthcare contributes about 5% of the world’s CO2 emissions, much of which comes from the energy required to run ventilation systems. By applying UV technology and smarter building control systems that consider more than just temperature and humidity, we have opportunities not only for cost savings but also for creating greener, more sustainable healthcare environments.

Georgia Lagoudas 1:01:26

Erik, can I add something here, and then maybe we can move on to another question, including some from the audience? Dr. Martinello, I wanted to expand on this thread about the tools we have in our toolbox and how they relate to change or advocacy for changing the status quo. One potential tool in the toolbox is increasing awareness of the problem—whether that’s through data collection like Dr. King described, personal stories, or information about indoor air quality. We need to turn something invisible, like air quality, into something visible and measurable.

I think one way to do this is to articulate specific characteristics of the air—whether it’s monitoring air change rates or even monitoring pathogens in the air. The United States Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health recently launched a major initiative to lead on sensing pathogens in the air.

With that in mind, I’m curious about your thoughts on how increasing awareness or gathering certain types of data could help drive change. Who are the key decision-makers in the ecosystem that need to receive this information to make changes in healthcare settings? I know that’s a big question, but I thought I’d put it out there. I’ll pause to see if someone is excited to tackle that first, or I might turn to Dr. King.

Plum Stone 1:03:09

From an advocacy perspective, what we’re trying to do is raise awareness of indoor air quality as an accessibility issue. Indoor air should be safe for everyone to breathe, and this is especially true in healthcare settings.

One of the things we’re focused on is reviewing the existing regulations and legislation. Here in Australia, we have the Disability Discrimination Act and workplace health and safety laws. I’m sure in the U.S., you have similar regulations under different names. The Disability Discrimination Act, for example, states that all public spaces should be universally safe and accessible for everyone, but it doesn’t yet include indoor air quality—and it should. People with chronic health conditions are at increased risk of poor health outcomes from infection, so ensuring safe indoor air quality in healthcare settings is crucial.

How do we ensure that people don’t come into a hospital with a broken wrist and leave with a COVID-19 infection or another infection that could significantly impact their health? As Bronwyn mentioned earlier, all spaces in a hospital should be considered high risk, but a lot of the messaging here focuses only on high-risk clinical settings, such as chemotherapy wards or transplant wards. Reception areas, cafes, and emergency departments often aren’t included in those considerations.

I’ll give you two examples. My husband, who is an excellent chef, recently cut his finger badly. He called me on a Sunday afternoon, saying he would have to go to the hospital. It became a decision for our family, because we had to weigh the risk—whether the injury was serious enough to justify the risk of exposure in the hospital. That shouldn’t be a consideration for any patient. You shouldn’t have to think, “Is this injury bad enough for stitches, or could I pick up something worse in the hospital?”

When my husband arrived at the hospital, they immediately placed him in an isolation room because they knew his health status—he’s a frequent visitor due to his chronic condition. He didn’t spend any time in the ED waiting room.

By comparison, when my son fell and broke his wrist a few months ago, we went to the hospital, and my husband attended as his carer. In that situation, my husband wasn’t whisked off to a private room like he was as a patient. But he should be safe whether he’s there as a patient or as a carer. The risk is the same in both situations.

What I’m trying to say is that we need to recognize indoor air quality as an accessibility issue. All spaces in a hospital should be safe, and all public spaces should be safe. Once we start framing it as an accessibility issue, everything falls into place. We just have to make indoor air safe for everyone.

Georgia Lagoudas 1:06:55

Thank you, Plum. That’s an inspirational way to think about it, though I know it’s a long road ahead. Any other comments from the panelists on this topic?

Richard Martinello 1:07:03

I think some of what Plum mentioned really resonated with me. In my introduction, I spoke a bit about severely immunocompromised patients, and over the last few decades, we’ve seen a shift where many of these patients, whose care used to be very hospital-centric, are now being treated in outpatient settings. So, as Plum said, it’s not just about hospitals, or even just certain areas within hospitals—we need to think about how we create better indoor air quality and safer environments across all healthcare settings. That’s incredibly important.

The other point I wanted to touch on is public awareness of this issue. Right now, our data streams are declining compared to what we had during the pandemic. We used to have more data from wastewater, more information about how many people were testing positive, and what proportion of tests were positive. But that’s diminishing.

In the U.S., much of our focus in infection prevention is hospital-centric. We pay attention to medical device-related infections, surgical site infections, and Clostridium difficile infections, but we don’t focus enough on healthcare-associated respiratory virus infections. Without that awareness, healthcare-associated respiratory infections don’t get the attention they deserve from hospital leadership or other stakeholders who could help incentivize creating safer indoor air spaces.

Roberta Smith 1:09:02

I’d like to comment on the importance of those other spaces as well. When we go to a hospital, we have infection preventionists, but in long-term care facilities, for instance, they’re just starting to get on board with infection prevention, and that’s a living space—it’s like a whole community. You have people in skilled nursing, and there might be assisted living spaces too, so you’ve got a mix of different communities in one facility. A lot of attention needs to be focused on those areas, as we saw during the pandemic, where the need for infection prevention became clear.

I’d also argue that dental facilities and clinics should be included in this discussion. There’s a lot of aerosolization going on in dental practices, and we need to monitor water lines, for example. Infection prevention measures need to extend beyond just hospitals and into everyday clinics and practices.

When we built our new building here in Routt County, I was able to talk to our county commissioners about ventilation, and we made sure to include a clinic space that pulls more air than the rest, for cases where someone with a contagious condition comes in. While it might be rare, we want to protect people in our small clinic in our small town. It’s important to promote infection prevention and healthy spaces beyond just hospitals.

Georgia Lagoudas 1:11:00

Thanks so much, Roberta. Let’s round this out—Dr. King, I know you wanted to comment. And then, Erik, maybe you can help us pull some questions from the audience.

Bronwyn King 1:11:09

Thank you so much. I just have two points to make. First, I completely echo Richard’s comments about the need to educate people on this issue. We have a little program here called “Make the Invisible Visible,” which I think Georgia will appreciate, given that’s exactly what she said earlier. It’s ridiculous that I have more monitoring in my house right now than we see in many public places. For example, I have this little CO2 monitor—it’s beautifully designed by two guys who started a social enterprise in Copenhagen. When CO2 levels get too high, the little canary on it “dies” and tips over. It’s a genius way to show when the air isn’t healthy, and it would be fantastic if every school, childcare center, and other public space had one so people could see when the air quality is poor and take action, like opening windows or going outside for a bit.

It doesn’t have to be overly technical. In fact, we’ve done this kind of community education with other issues—like tobacco control, drink driving, and sun safety. In Victoria, everyone knows the blood alcohol limit is 0.05. We know what SPF means when we’re buying sunscreen. In the same way, we need people to recognize something like 800 ppm for CO2—maybe they don’t need to know all the technical details, but they should know that 800 means the air isn’t fresh. Simple messages like that can help.

Second, Georgia, you asked about how we can get leaders to act on the data we provide. That’s the frustrating thing for scientists—data alone doesn’t motivate people. There’s some kind of magic that has to happen between presenting the data and getting people to act. Part of that is storytelling. One powerful story can move people much more than a stack of brilliant research papers. It’s important to make leaders feel like they have skin in the game. Plum mentioned the issue of “othering,” where people think, “It’s only happening to others, so I don’t need to worry.” We need to make people realize that this affects everyone.

We also need to speak the language of leaders. One of those languages is inclusion—leaders talk a lot about inclusion, and you can’t have an inclusive environment without addressing clean air. Another is workplace health and safety, which every leader understands. Finally, we need to talk about money. Leaders want to know what the return on investment is. While clean air does involve upfront costs, the long-term benefits are massive. There are economic models showing that for every dollar spent, you get at least $10 back, and in some cases, up to $100 back over time. These benefits continue in perpetuity. So, we need to be more strategic about bridging the gap between data and action.

Erik Malstrom 1:15:24

Right. So many great comments there, and I emphatically agree with much of it myself. But I’m going to pick up on the money, because I love the money, and that’s often where the rubber meets the road with these initiatives. We received a question from Chris Hilliker related to economics: What are some cost-benefit analyses for added filtration, whether standalone or integrated, from the lens of each of your professions? For example, energy consumption, HVAC efficiency, equitable delivery of clean air around a room, the cost to society, and the cost to employers.

This touches on the different components of the economic piece—capital costs, ongoing operating costs, and the distribution of benefits across building owners, patients, workers, and society. When we think about filtration or other effective controls, how would you quantify the benefits in dollar terms, whether U.S. dollars or Aussie dollars, in a way that would move the needle for leadership to act?

I’ll open it up to Bronwyn first, since you just touched on this in your comments, and then we’ll hear from others.

Bronwyn King 1:16:57

Look, I think there’s been economic modeling done all around the world. I’ve got my little booklet here with some stats I’d like to read out because I don’t have all of these memorized. This is from the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab in the U.S., specifically from their Indoor Air Quality Scientific Findings Resource Bank. They estimated that improving ventilation rates in just one-third of U.S. offices—the ones with the worst ventilation—would result in an annual benefit of $13.5 billion USD. So, the impacts are massive—really significant.

Every paper I’ve seen shows enormous benefits, and often these studies focus on a small slice of the overall potential. For example, many of you might be familiar with Dr. Richard Bruns from the U.S., who’s done incredible cost-benefit modeling for different indoor air quality measures. His analysis found a cost-benefit ratio of $1 in, $10 out. But that only looked at a small percentage of U.S. buildings, only considered indoor air quality improvements during winter months, and only focused on reducing COVID-19 infections. In reality, the benefits of improving indoor air quality would extend far beyond COVID-19, reducing the risk of other infectious diseases and indoor air pollution.

So, while we do need more robust data, I think there’s already enough evidence out there to justify getting started now.

Erik Malstrom 1:18:45

Great. Over to you, Plum. I know you’ve been doing some interesting analysis. Care to share?

Plum Stone 1:18:50

I’m happy to share with everyone on the call that next month we’re launching a report titled Safer Shared Air: A Critical Accessibility and Inclusion Issue. In that report, we’ve included some new cost-benefit analysis. For those who may not have seen it, about three weeks ago, the Facilities Management Association of New Zealand released a cost-benefit analysis for investing in indoor air quality in New Zealand. I’ll put that link in the chat.

Additionally, in August, the Medical Journal of Australia published a paper focusing on the costs of long COVID on the Australian economy, which showed that long COVID alone cost the Australian economy $10 billion in 2022.

The new analysis in our report combines the New Zealand data with the Medical Journal of Australia findings. It demonstrates that the benefit-to-cost ratio of investing in indoor air quality, specifically to prevent COVID-19 and long COVID—without even accounting for other costs associated with poor indoor air quality—would deliver a return on investment in the range of $25 to $50 billion. This is a huge figure, and it’s only considering one small aspect of the broader benefits that improved air quality would bring.

We need more data, and in our report, we’ll be calling for the Productivity Commission here to conduct a more extensive analysis. I know Lydia Morawska’s group at Thrive is also working on cost-benefit analyses, so more information is on the way.

But ultimately, we need to remember that indoor air quality is an accessibility issue, and regardless of the costs, it’s something we need to address because human life and health are at risk. The fact that we can generate a financial return on investment is obviously a great bonus, but there’s also a significant social return on investment to consider.

Erik Malstrom 1:21:15

I want to share one other cost factor that wasn’t mentioned but tends to get people’s attention in healthcare systems—liability protection. In healthcare settings, when people get infected or when problems arise, whether in hospitals or other facilities, liability becomes a serious issue. These facilities are subject to more stringent regulations than other buildings, though, arguably, they don’t go far enough. In the U.S., at least, we’ve seen numerous instances where healthcare-associated infections can be grounds for lawsuits, which can be extremely costly.

Richard, from your perspective, since you’re within a healthcare system, is liability something that affects how systems prioritize the urgency and seriousness of addressing these issues?

Richard Martinello 1:22:22

I think during COVID-19, we saw many examples where healthcare systems, particularly long-term care facilities, were found to be negligent in how they managed the virus. This led to widespread outbreaks and, unfortunately, the expected morbidity and mortality.

One thing I’ve noticed is that as evidence grows showing not only the cost-effectiveness but also the potential to prevent costs, getting these new technologies integrated into building design codes and guidelines will be critical. In many healthcare settings I’ve worked in, we budget for new construction or renovation at a certain amount, but invariably the actual costs exceed the budget. That makes it extremely difficult to retain what might be considered “extras” that go beyond building codes.

Getting these newer technologies into the building codes will be a critical step toward creating safer spaces.

Roberta Smith 1:23:46

And if I could just jump in here, I agree with that. Technology does have a place, especially if you have a specific problem. There are so many different technologies out there, but it’s also important to make sure we have the scientific evidence behind these solutions before they’re implemented. That can actually be a potential cost savings as well—if you invest in a device or solution that ultimately doesn’t work for your facility, it’s a wasted expense. Doing that research ahead of time to ensure the solution fits your facility and its needs is definitely a financial consideration when it comes to indoor air quality solutions.

Erik Malstrom 1:24:38

Well, we have five minutes left, and while we could keep going, I want to respect everyone’s time. So, I’m going to invite Dr. Claire Bird from IBEC to give us a final question. Over to you, Claire.

Claire Bird 1:25:00

Hi everyone, and thank you so much for what’s been an absolutely incredible session. Based on everything that’s been discussed, I’d like to raise a question from the chat that ties into several topics we’ve covered today.

We’ve talked about the lived experiences of our panelists, both professional and personal, and we’ve discussed protecting people from near-field transmission through measures like masks. We’ve also touched on increasing ventilation and diluting pathogens in the air, as well as the role of technology.

My question for all of you is this: if we take a layered approach, is that the right answer? And if so, what do you feel are the most important layers in this approach?

Bronwyn King 1:26:04

I can jump in quickly to finish off. For me, the key components would be education, the implementation of indoor air quality standards, and monitoring. I think all three go hand in hand. If we’re going to monitor, people need to understand what the numbers mean and why it matters. We’ve got to educate—nothing really happens unless people understand the “why.” Without that understanding, they won’t be moved to act.

As for standards, they are crucial. Guidelines alone aren’t enough. We need proper, legally enforced standards, and while we might need some transition time for buildings and societies to catch up, ultimately we need robust, living, breathing standards that become a routine part of life globally.

Thank you.

Claire Bird 1:26:59

Thanks, Bronwyn. Does anyone else have any closing thoughts or words on that?

Roberta Smith 1:27:05

I’d like to add to that as well. I do think our standards and guidelines need to be revisited and updated to keep pace with what we’re seeing, especially as we deal with emerging pathogens like COVID-19. We need to be able to control what we can—starting with our ventilation standards and ensuring we’re doing the best for our facilities.

Meeting the guidelines, understanding them, and emphasizing education are critical. We know from the hierarchy of controls that PPE is at the bottom because we’re human, and we don’t always wear it properly. So, where can we strengthen those layers of protection? It’s that Swiss cheese model, and I think ventilation, engineering controls, and updated guidelines really rise to the top for me.

Richard Martinello 1:28:13

I agree with all of those points. I just want to add that, at least in the United States, we need ways to incentivize healthcare systems to ensure they’re creating safer spaces with better indoor air quality. Right now, we don’t have those incentives in place.

Claire Bird 1:28:31

Thank you. Thank you, Dr. Martinello. Any closing words?

Plum Stone 1:28:36

There was a question in the chat about ASHRAE 241, which really focuses on infection risk management mode. It should apply at all times. We need a performance standard that enables facilities to meet that infection risk management mode because we have to assume that even in the absence of an obvious pathogen or emerging pathogen, there will always be someone in a space who is at increased risk of poor health outcomes from infection. Therefore, infection risk management mode should apply at all times, and the only way to achieve that is through performance standards.

So, I agree with everyone—we need it today.

Claire Bird 1:29:26

Thank you all very much. If anyone has any questions that didn’t get addressed, please send an email to info@weareibec.org, and we’ll make sure to pass them on to the relevant speaker or panelist. Again, a huge thank you to everyone, especially to Georgia for leading this absolutely fantastic session. I’ll now hand it over to Stéphane to close us out. And thank you all for attending.

Kenneth Martinez 1:29:53

Thank you, Claire. Hello, everyone. My name is Ken Martinez, and I currently serve as the President of IBEC. As we close this wonderful event, I want to extend a heartfelt thank you to our outstanding and insightful speakers—Bronwyn, Roberta, Plum, and Richard—as well as our generous and sharp moderators, Georgia and Erik. Thank you all.

Secondly, I want to thank each and every participant for taking the time to join us today. Your contributions help us extend a vibrant and inclusive scientific community that provides meaningful experiences and knowledge to benefit everyone involved and beyond. We welcome all of you to join us as IBEC members, and if you’re not already a member, we encourage you to consider joining, or even more, to sponsor and contribute to our events and initiatives.

I also want to inform all participants that the event videos will be made available on the IBEC website, and both Stéphane and I have posted the link in the chat. Feel free to revisit the content and share it within your professional circles.

As a member, you have the opportunity to connect with global thought leaders, exchange ideas across multiple disciplines, and receive valuable communications. By sponsoring our events, your brand will gain visibility in the indoor air quality space while presenting your innovative products, projects, or services to a wide and highly engaged audience.

I’d like to once again thank this event’s sponsor, the American Industrial Hygiene Association, and I also want to thank our Science Advisory Board members for their support and insights throughout the year. The SAB is composed of an outstanding, multidisciplinary membership from around the world, which explores emerging trends, technologies, and research gaps while seeking opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration.

Thank you all for being part of our community. We look forward to welcoming you to our upcoming events and initiatives, where you can connect with like-minded individuals and explore science across a wide range of solutions, activities, and opportunities.

Have a great rest of your day, and thank you again for joining us.

Watch the other sessions of the 6-part IAQ CLEAN Lessons Learned series

Navigating the H5N1 Challenge

Go to this sessionBridging the Gap Between Current IAQ Assessments and Evolving Biosensing Technologies in Built Environments

Go to this sessionVentilation as a Key Defense Against Infectious Diseases

Go to this sessionUnraveling Infectious Disease Transmission in the Built Environment

Go to this sessionIndoor Air Quality as a Public Health Strategy to Reduce the Risk of Infectious Disease Transmission in the Built Environment

Go to this sessionSponsor Spotlight

American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA)

AIHA is the association for scientists and professionals committed to preserving and ensuring occupational and environmental health and safety (OEHS) in the workplace and community. Founded in 1939, we support our members with our expertise, networks, comprehensive education programs, and other products and services that help them maintain the highest professional and competency standards. More than half of AIHA’s nearly 8,500 members are Certified Industrial Hygienists, and many hold other professional designations. AIHA serves as a resource for those employed across the public and private sectors and the communities in which they work.

Have a question about the event?

Connect with IBEC experts directly! Drop your queries below, and let's further the dialogue on preventing the spread of infectious diseases.